The Habit

It's my wife

And it's my life

- Velvet Underground ( Heroin)

And it's my life

- Velvet Underground ( Heroin)

They say it'll kill me

But the don't say when

- Traditional

-

But the don't say when

- Traditional

-

Greetings

They say that before you can quit your addiction, you have to recognize it. I'm pretty sure that most of us don't really want to accept the truth. Not so much that we are destroying the planet. That's pretty obvious. But it's our lifestyle that's doing it. And we just don't want to give it up. So we pretend it's not a problem

Doesn't matter whether it's a progressive, a socialist, or a libertarian. We still want to " good life" and that trumps everything else. So we resort to finger pointing.

"We have a situation, then, where one half of the population says it is not happening, and the other half says it is happening but fighting it doesn’t have to change our way of life. Like a dysfunctional and enabling married couple, the bickering and finger-pointing, and anger ensures that nothing has to change and that no one has to actually look deeply at themselves, even as the wheels are falling off the family-life they have co-created. And so do Democrats and Republicans stay together in this unhappy and unproductive place of emotional self-protection and planetary ruin."

Here are some of the stories we tell ourselves, to allow us to continue this behavior. How to kick the habit? That's a little tougher.

"The problem is daunting; making changes can be difficult.[vii] But not only can you do something, you can’t not do anything. Either you will continue to buy, use, and consume as if there is no tomorrow; or you will make substantial changes to the way you live. Both choices are “doing something.” Either you will emit far more CO2 than people in most parts of the globe; or you will bring your carbon footprint to an equitable level

------------

Six Myths About Climate Change that Liberals Rarely Question

Myth #1: Liberals Are Not In Denial

“We will not apologize for our way of life” –Barack Obama

The conservative denial of the very fact of climate change looms large in the minds of many liberals. How, we ask, could people ignore so much solid and unrefuted evidence? Will they deny the existence of fire as Rome burns once again? With so much at stake, this denial is maddening, indeed. But almost never discussed is an unfortunate side-effect of this denial: it has all but insured that any national debate in America will occur in a place where most liberals are not required to challenge any of their own beliefs. The question has been reduced to a two-sided affair—is it happening or is it not—and liberals are obviously on the right side of that.

If we broadened the debate just a little bit, however, we would see that most liberals have just moved a giant boat-load of denial down-stream, and that this denial is as harmful as that of conservatives. While the various aspects of liberal denial are my main overall topic, here, and will be addressed in our following five sections, they add up to the belief that we can avoid the most catastrophic levels of climate disruption without changing our fundamental way of life. This is myth is based on errors that are as profound and basic as the conservative denial of climate change itself.

But before moving on, one more point about liberal and conservative denial: Naomi Klein has suggested that conservative denial may have its roots, it will surprise many liberals, in some pretty clear thinking. [i] At some level, she has observed, conservatives climate deniers understand that addressing climate change will, in fact, change our way of life, a way of life which conservatives often view as sacred. This sort of change is so terrifying and unthinkable to them, she argues, that they cut the very possibility of climate change off at its knees: fighting climate change would force us to change our way of life; our way of life is sacred and cannot be questioned; ergo, climate change cannot be happening.

We have a situation, then, where one half of the population says it is not happening, and the other half says it is happening but fighting it doesn’t have to change our way of life. Like a dysfunctional and enabling married couple, the bickering and finger-pointing, and anger ensures that nothing has to change and that no one has to actually look deeply at themselves, even as the wheels are falling off the family-life they have co-created. And so do Democrats and Republicans stay together in this unhappy and unproductive place of emotional self-protection and planetary ruin.

Myth #2: Republicans are Still More to Blame

“Yes, America does face a cliff -- not a fiscal cliff but a set of precipices [including a carbon cliff] we'll tumble over because the GOP's obsession over government's size and spending has obscured them.” -Robert Reich

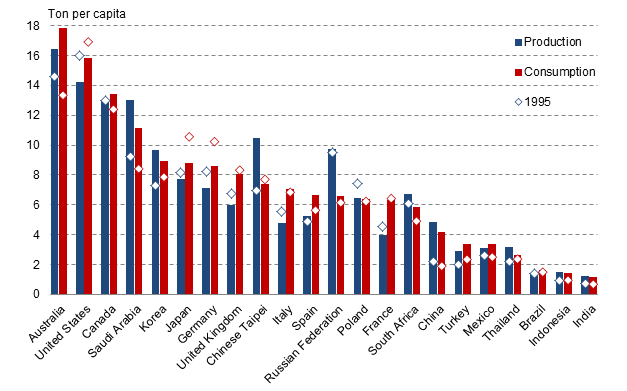

It is true that conservative politicians in the United States and Europe have been intent on blocking international climate agreements; but by focusing on these failed agreements, which only require a baby-step in the right direction, liberals obliquely side-step the actual cause of global warming—namely, burning fossil fuels. The denial of climate change isn’t responsible for the fact that we, in the United States, are responsible for about one quarter of all current emissions if you include the industrial products we consume (and an even greater percentage of all emissions over time), even though we make up only 6% of the world’s population. Our high-consumption lifestyles are responsible for this. Republicans do not emit an appreciably larger amount of carbon dioxide than Democrats.

Because pumping gasoline is our most direct connection to the burning of fossil fuels, most Americans overemphasize the significance of what sort of car we drive and many liberals might proudly point to their small economical cars or undersized SUVs. While the transportation sector is responsible for a lot of our emissions, the carbon footprint of any one individual has much more to do with his or her overall levels of consumption of all kinds—the travel (especially on airplanes), the hotels and restaurants, the size and number of homes, the computers and other electronics, the recreational equipment and gear, the food, the clothes, and all the other goods, services, and amenities that accompany an affluent life. It turns out that the best predictor of someone’s carbon footprint is income. This is true whether you are comparing yourself to other Americans or to other people around the world. Middle-class American professionals, academics, and business-people are among the world’s greatest carbon emitters and, as a group, are more responsible than any other single group for global warming, especially if we focus on discretionary consumption. Accepting the fact of climate change, but then jetting off to the tropics, adding another oversized television to the collection, or buying a new Subaru involves a tremendous amount of denial. There are no carbon offsets for ranting and raving about conservative climate-change deniers.

Myth #3: Renewable Energy Can Replace Fossil Fuels

“We will harness the sun and the winds and the soil to fuel our cars and run our factories.” –Barack Obama

This is a hugely important point. Everything else hinges on the myth that we might live a lifestyle similar to our current one powered by wind, solar, and biofuels. Like the conservative belief that climate change cannot be happening, liberals believe that renewable energy must be a suitable replacement. Neither view is particularly concerned with the evidence.

Conventional wisdom among American liberals assures us that we would be well on our way to a clean, green, low-carbon, renewable energy future were it not for the lobbying efforts of big oil companies and their Republican allies. The truth is far more inconvenient than this: it will be all but impossible for our current level of consumption to be powered by anything but fossil fuels. The liberal belief that energy sources such as wind, solar, and biofuels can replace oil, natural gas, and coal is a mirror image of the conservative denial of climate change: in both cases an overriding belief about the way the world works, or should work, is generally far stronger than any evidence one might present. Denial is the biggest game in town. Denial, as well as a misunderstanding about some fundamental features of energy, is what allows someone like Bill Gates assume that “an energy miracle” will be created with enough R & D. Unfortunately, the lessons of microprocessors do not teach us anything about replacing oil, coal, and natural gas.

It is of course true that solar panels and wind turbines can create electricity, and that ethanol and bio-diesel can power many of our vehicles, and this does lend a good bit of credibility to the claim that a broader transition should be possible—if we can only muster the political will and finance the necessary research. But this view fails to take into account both the limitations of renewable energy and the very specific qualities of the fossil fuels around which we’ve built our way of life. The myth that alternative sources of energy are perfectly capable of replacing fossil fuels and thus of maintaining our current way of life receives widespread support from our President to leading public intellectuals to most mainstream journalists, and receives additional backing from our self-image as a people so ingenious that there are no limits to what we can accomplish. That fossil fuels have provided us with a one-time burst of unrepeatable energy and affluence (and ecological peril) flies in the face of nearly all the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves. Just starting to dispel this myth requires that I go into the issue a bit more deeply and at greater length.

Because we have come to take the power and energy-concentration of fossil fuels for granted, and see our current lifestyle as normal, it is easy to ignore the way the average citizens of industrialized societies have an unprecedented amount of energy at their disposal. Consider this for a moment: a single $3 gallon of gasoline provides the equivalent of about 80 days of hard manual labor. Fill up your 15 gallon gas tank in your car, and you’ve just bought the same amount of energy that would take over three years of unremitting manual labor to reproduce. Americans use more energy in a month than most of our great-grandparents used during their whole lifetime. We live at a level, today, that in previous days could have only been supported by about 150 slaves for every American—though even that understates it, because we are at the same time beneficiaries of a societal infrastructure that is also only possible to create if we have seemingly limitless quantities of lightweight, relatively stable, easily transportable, and extremely inexpensive ready-to-burn fuel like oil or coal.

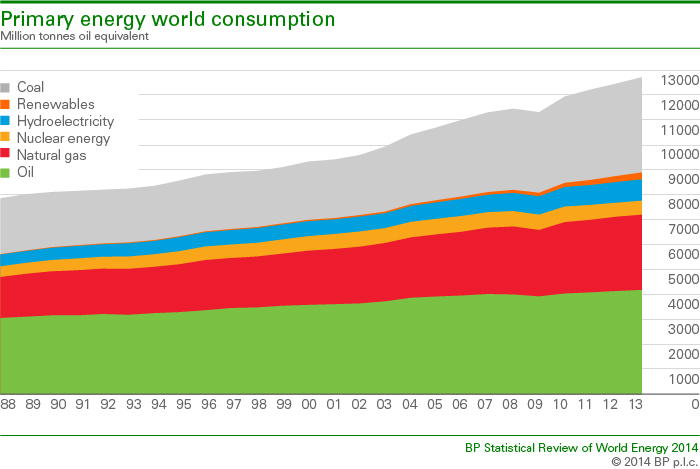

A single, small, and easily portable gallon of oil is the product of nearly 100 tons of surface-forming algae (imagine 5 dump trucks full of the stuff), which first collected enormous amounts of solar radiation before it was condensed, distilled, and pressure cooked for a half-billion years—and all at no cost to the humans who have come to depend on this concentrated energy. There is no reason why we should be able to manufacture at a reasonable cost anything comparable. And when we look at the specific qualities of renewable energy with any degree of detail we quickly see that we have not. Currently only about a half of a percent of the total energy used in the United States is generated by wind, solar, biofuels, or geothermal heat. The global total is not much higher, despite the much touted efforts in Germany, Spain, and now China. In 2013, 1.1% of the world’s total energy was provided by wind and only 0.2% by solar.[ii] As these low numbers suggest, one of the major limitations of renewable energy has to do with scale, whether we see this as a limitation in renewable energy itself, or remind ourselves that the expectations that fossil fuels have helped establish are unrealistic and unsustainable.

University of California physics professor Tom Murphy has provided detailed calculations about many of the issues of energy scale in his blog, “Do the Math.” With the numbers adding up, we are no longer able to wave the magic wand of our faith in our own ingenuity and declare the solar future would be here, but for those who refuse to give in the funding it is due. Consider a few representative examples: most of us have, for instance, heard at some point the sort of figure telling us that enough sun strikes the Earth every 104 minutes to power the entire world for a year. But this only sounds good if you don’t perform any follow-up calculations. As Murphy puts it,

"As reassuring as this picture is, the photovoltaic area [required] represents more than all the paved area in the world. This troubles me. I’ve criss-crossed the country many times now, and believe me, there is a lot of pavement. The paved infrastructure reflects a tremendous investment that took decades to build. And we’re talking about asphalt and concrete here: not high-tech semiconductor. I truly have a hard time grasping the scale such a photovoltaic deployment would represent. And I’m not even addressing storage here." [iii]

In another post,[iv] Murphy calculates that a battery capable of storing this electricity in the U.S. alone (otherwise no electricity at night or during cloudy or windless spells) would require about three times as much lead as geologists estimate may exist in all reserves, most of which remain unknown. If you count only the lead that we’ve actually discovered, Murphy explains, we only have 2% of the lead available for our national battery project. The number are even more disheartening if you try to substitute lithium ion or other systems now only in the research phase. The same story holds true for just about all the sources that even well-informed people assume are ready to replace fossil fuels, and which pundits will rattle off in an impressively long list with impressive sounding numbers of kilowatt hours produced. Add them all up--even increase the efficiency to unanticipated levels and assume a limitless budget--and you will naturally have some big-sounding numbers; but then compare them to our current energy appetite, and you quickly see that we still run out of space, vital minerals and other raw materials, and in the meantime would probably have strip-mined a great deal of precious farmland, changed the earth’s wind patterns, and have affected the weather or other ecosystems in ways not yet imagined.

But the most significant limitation of fossil fuel’s alleged clean, green replacements has to do with the laws of physics and the way energy, itself, works. A brief review of the way energy does what we want it to do will also help us see why it takes so many solar panels or wind turbines to do the work that a pickup truck full of coal or a small tank of crude oil can currently accomplish without breaking a sweat. When someone tells us of the fantastic amounts of solar radiation that beats down on the Earth each day, we are being given a meaningless fact. Energy doesn’t do work; only concentrated energy does work, and only while it is going from its concentrated state to a diffuse state—sort of like when you let go of a balloon and it flies around the room until its pressurized (or concentrated) air has joined the remaining more diffuse air in the room.

When we build wind turbines and solar panels, or grow plants that can be used for biofuels, we are “manually” concentrating the diffuse energy of the sun or in the wind—a task, not incidentally, that requires a good deal of energy. The reason why these efforts, as impressive as they are, pale in relationship to fossil fuels has to do simply with the fact that we are attempting to do by way of a some clever engineering and manufacturing (and a considerable amount of energy) what the geology of the Earth did for free, but, of course, over a period of half a billion years with the immense pressures of the planet’s shifting tectonic plates or a hundred million years of sedimentation helping us out. The “normal” society all of us have grown up with is a product of this one-time burst of a pre-concentrated, ready-to-burn fuel source. It has provided us with countless wonders; but used without limits, it is threatening all life as we know it.

Myth 4: The Coming “Knowledge Economy” Will be a Low-Energy Economy

"The basic economic resource - the means of production - is no longer capital, nor natural resources, nor labor. It is and will be knowledge." -Peter Drucker

“The economy of the last century was primarily based on natural resources, industrial machines and manual labor. . . . Today’s economy is very different. It is based primarily on knowledge and ideas — resources that are renewable and available to everyone.” -Mark Zuckerberg

A “low energy knowledge economy,” when promised by powerful people like Barack Obama, Bill Gates, or Mark Zuckerberg, may still our fears about our current ecological trajectory. At a gut level this vision of the future may match the direct experience of many middle-class American liberals. Your father worked in a smelting factory; you spend your day behind a laptop computer, which can, in fact, be run on a very small amount of electricity. Your carbon footprint must be lower, right? Companies like Apple and Microsoft round out this hopeful fantasy with their clever and inspiring advertisements featuring children in Africa or China joining this global knowledge economy as they crowd cheerfully around a computer in some picturesque straw-hut school room.

But there’s a big problem with this picture. This global economy may seem like it needs little more than an army of creative innovators and entrepreneurs tapping blithely on laptop computers at the local Starbucks. But the real global economy still requires a growing fleet of container ships—and, of course, all the iron and steel used to build them, all the excavators used to mine it, all the asphalt needed to pave more of the world. It needs a bigger and bigger fleet of UPS trucks and Fed Ex airplanes filling the skies with more and more carbon dioxide, it needs more paper, more plastic, more nickel, copper, and lead. It requires food, bottled water, and of course lots and lots of coffee. And more oil, coal, and natural gas. As Juliet Schor reports, each American consumer requires “132,000 pounds of oil, sand, grain, iron ore, coal and wood” to maintain our current lifestyle each year. That adds up to “an eye-popping 362 pounds a day.”[v] And the gleeful African kids that Apple asks us to imagine joining the global economy? They are far more likely to slave away in a gold mine or sift through junk hauled across the Atlantic looking for recyclable materials, than they are to be device-sporting global entrepreneurs. The Microsoft ads are designed for us, not them. Meanwhile, the numbers Schor reports are not going down in the age of “the global knowledge economy,” a term which should be consigned to history’s dustbin of misleading marketing slogans.

The “dematerialized labor” that accounts for the daily toil of the American middle class is, in fact, the clerical, management and promotional sector of an industrial machine that is still as energy-intensive and material-based as it ever was. Only now, much of the sooty and smelly part has been off-shored to places far, far away from the people who talk hopefully about a coming global knowledge economy. We like to pretend that the rest of the world can live like us, and we have certainly done our best to advertise, loan, seduce, and threaten people across the world to adopt our style, our values, and our wants. But someone still has to do the smelting, the welding, the sorting, and run the ceaseless production lines. And, moreover, if everyone lived like we do, took our vacations, drove our cars, ate our food, lived in our houses, filled them with oversized TVs and the endless array of throwaway gadgetry, the world would use four times as much energy and emit nearly four times as much carbon dioxide as it does now. If even half the world’s population were to consume like we do, we would have long since barreled by the ecological point of no-return.

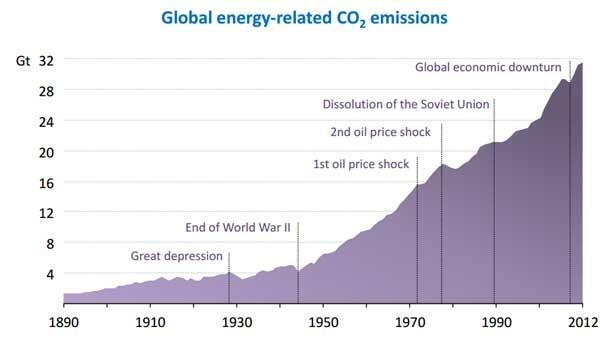

Economists speak reverently of a decoupling between economic growth and carbon emissions, but this decoupling is occurring at a far slower rate than the economy is growing. There has never been any global economic growth that is not also accompanied by increased energy use and carbon emissions. The onlyyearly decreases in emissions ever recorded have come during massive recessions.

Myth 5: We can Reverse Global Warming Without Changing our Current Lifestyles

“Saving the planet would be cheap; it might even be free. . . . [It] would have hardly any negative effect on economic growth, and might actually lead to faster growth” –Paul Krugman

The upshot of the previous sections is that the comforts, luxuries, privileges, and pleasures that we tell ourselves are necessary for a happy or satisfying life are the most significant cause of global warming and that unless we quickly learn to organize our lives around another set of pleasures and satisfactions, it is extremely unlikely that our children or grandchildren will inherit a livable planet. Because we are falsely reassured by liberal leaders that we can fight climate change without any inconvenience, it bears repeating this seldom spoken truth. In order to adequately address climate change, people in rich industrial nations will have to reduce current levels of consumption to levels few are prepared to consider. This truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it.[vi]

Global warming is not complicated: it is caused mainly by burning fossil fuels; fossil fuels are burned in the greatest quantity by wealthy people and nations and for the products they buy and use. The larger the reach of a middle-class global society, the more carbon emissions there have been. While conservatives deny the science of global warming, liberals deny the only real solution to preventing its most horrific consequences—using less and powering down, perhaps starting with the global leaders in style and taste (as well as emissions), the American middle-class. In the meantime we continue to pump more and more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere with each passing year.

Myth 6: There is Nothing I Can Do.

The problem is daunting; making changes can be difficult.[vii] But not only can you do something, you can’t not do anything. Either you will continue to buy, use, and consume as if there is no tomorrow; or you will make substantial changes to the way you live. Both choices are “doing something.” Either you will emit far more CO2 than people in most parts of the globe; or you will bring your carbon footprint to an equitable level. Either you will turn away, ignore the warnings, bury your head in the sand; or you will begin to take a strong stance on perhaps the most significant moral challenge in the history of humanity. Either you will be a willing party to the most destructive thing humans have ever done; or you will resist the wants, the beliefs, and the expectations that are as important to a consumption-based global economy as the fossil fuels that power it. As Americans we have already done just about everything possible to bring the planet to the brink of what scientists are now calling “the sixth great extinction.” We can either keep on doing more of the same; or we can work to undo the damage we have done and from which we have most benefitted.

[ii] http://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/about-bp/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy.html

[iii] http://physics.ucsd.edu/do-the-math/2011/09/dont-be-a-pv-efficiency-snob/#sthash.C1jCJK3V.dpuf).

[v] Schor, Juliet. Plentitude, p. 44.

[vi] As Flannery O’Connor would say.

[vii] Making changes is especially difficult to do alone. Fortunately, community efforts such as Transition Towns are popping up around the globe, giving people both practical help and the emotional support necessary to tackle such a large task.