Food…

Along with water and energy, which are related to its production, it is one of the key commodities necessary to keep the world’s 7.1 billion people alive, healthy and happy. Its price and availability can determine the fate of nations and the stability of the world’s economic system. Rising prices mean risk of increasing poverty, risk of political instability and, in the worst instances, a creeping spread of hunger and malnutrition about the globe.

And ever since the year 2000 world food prices have been steadily and inexorably rising.

(UN FAO Food Price Index through February of 2014. Image source:

UN FAO.)

The UN FAO Index — An Indicator for Global Crisis

The United Nations provides a valuable index that comprehensively assesses the overall cost of food in both real and nominal terms. Managed by the

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the food price index has been tracking global indicators for this valuable commodity since 1961.

The FAO Index emerged in a world that hosted 3 billion people. A world that was just beginning to realize the strengths and limitations of its new, mechanized, fossil fuel-dependent, civilization. A world where new fossil water resources and slow to recharge groundwater were being tapped through drilling. A world where farming was expanding into even the most marginal and vulnerable of regions even as forests continued to be converted into farmland at a stunning rate.

From a period of the 1960s on into the first years of the 1970s, the nascent FAO price index recorded stable if moderately high global food prices. By the 1970s, food prices spiked along with the cost of energy during an oil crisis related to a

Growth Shock as US and western energy production encountered a series of difficult to cross boundary limits.

The First Test — 1970s Energy and Climate Crisis

The FAO also emerged in a world where agriculture was heavily dependent on fossil material and energy inputs — for machinery, pesticides, and for fertilizer. This single commodity dependence meant that any spike in oil prices also had a deleterious effect on food access. And energy price spike after energy price spike occurred throughout the 1970s. A first warning that such a high level of reliance on just one commodity — oil — was a clear and critical weakness for the global economic and food distribution system.

At the same time, an intense drought swept over Africa. The rains that annually drenched the Sahel region faded and, then, for a period of about a decade, simply failed. The energy crisis combined with severe decadal climate shifts in Africa to further stress world food markets already reeling under oil price shocks. Higher prices, political instability and widespread hunger soon followed.

During this time, the link between human fossil fuel emissions and a potential to radically alter the climate in a way that was far more hostile to traditional agriculture was mostly unexplored. But despite this general lack of awareness, changes were already lining up that would have severe consequences for human agriculture within only a few decades. A then less visible, but no less important, weakness resulting from industrial agriculture’s, and much of modern civilization’s, reliance on oil, gas and coal. Fuels whose endlessly ramping use created long-term and ever increasing damage to environments in which human agriculture could be reasonably expected to exist.

Rise From Crisis Without Addressing Underlying Vulnerability

Political pressure was put on the Middle East to make energy more cheaply and readily available. Forests were cut down in South America to make room for more farmland. Saudi Arabia mined fossil water to farm its deserts. Meanwhile, the rains eventually returned to Africa and so prices again fell to far more affordable levels during the 1980s and 1990s. But the key weaknesses — reliance on fossil fuels for agriculture, an immense world population that jumped to 4, 5 and then 6 billion, a host of problems and vulnerabilities emerging from big industrial farms, and increasing agricultural vulnerability to water scarcity and related climate shifts were not addressed.

So as the world entered the first decade of the new millennium and signs of crisis began to again emerge, it found itself radically unprepared to deal with what was shaping up to be a more vicious repeat of the shocks experienced during the 1970s.

Energy Shocks, Extreme Weather, Consumption Changes, 7 Billion People

By the middle of the decade, a series of crisis points had been reached. Worldwide demand for both food and energy was raging. Populations were nearing 7 billion souls. Oil price increases were leading more nations to use farmland for biofuels production creating a competition for land use between fuels and food. Australia was suffering its worst drought in 1,000 years and many other regions of the world were likewise sporadically hit. But the big, severe, widespread droughts would wait for next decade to emerge with even greater force and rapacity.

By 2007, world oil prices were screaming toward record levels and an already climate and demand stressed food market rapidly followed. By 2008, the FAO index had surged to a record level of 201. Such a large jump had numerous and far-reaching effects. Hunger again became an issue of serious concern in Africa and, sporadically, various countries began to see food riots as the distribution system painfully rebalanced to reflect new levels of increased demand and struggling output. Global economic recession immediately ensued and prices were drawn down through the economically vicious process of demand destruction.

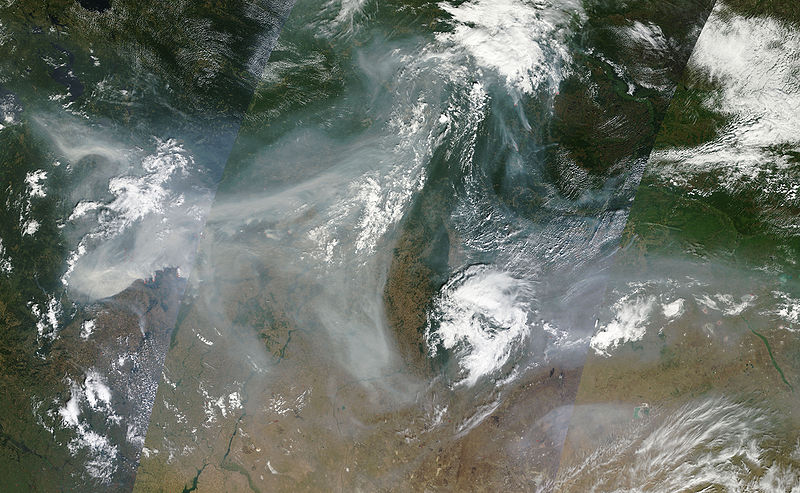

(Satellite shot of smoke from massive wildfires raging across Russia during 2010. The largest smoke plume in this image is 3,000 kilometers in length, about the distance between Los Angeles and Chicago. Image source:

Lance-Modis.)

Rising Threats for the Current Day

The world’s primary response to this major price spike was to simply plant more land. But as this new rush occurred, extreme weather got a radical boost. Sea ice losses, by end of summer 2012, had totaled more than 50% in area and extent values since 1979 while volume measures had brutally fallen by over 80%.

As a result, the Arctic had lost about 4% of its albedo and was undergoing a period of rapid heat amplification. These changes would result in more persistent and severe Jet Stream patterns that would deliver an increasingly extreme battery of droughts and deluges to the Northern Hemisphere. Meanwhile, warming had now resulted in an amplification of the global hydrological cycle by 6%. This amplification meant drying of the land came on more rapidly, setting the stage for intense drought initiation even in regions that weren’t seeing more stuck weather patterns.

For by February of this year the world FAO index had risen to 208.1 — a level very close to 210 which is considered to be the point that high food prices begin to result in the potential for major social unrest worldwide.

High Risk Outlook for 2014

With so many regions experiencing drought, with human-caused climate change playing havoc with the world’s weather,

and with the rising risk of a moderate-to-strong El Nino emerging in the Eastern Pacific, the world appears to be entering yet one more period of high risk for another major food shock. El Nino is traditionally known to produce drought in Australia and Southeast Asia. And while it is has not historically tended to coincide with drought in Russia and Eastern Europe, it does tend to shift weather patterns toward hot in those regions. With the hydrological cycle amped up by human-caused climate change and with ridges/blocking patterns more prevalent due to added atmospheric heat content and sea ice loss, it might be wise to consider the 2010 spate of extreme drought and fires in this region a potential risk as the year and a likely El Nino progresses.

Links:

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home